Will Proposed ASAT Ban Finally Elicit Proper Space Policy?

By Abby Proch, former editor

Slowly but surely, nations are coming together to talk space policy. With the proliferation of low Earth orbit (LEO), the threat of accumulating space junk, and the vulnerabilities of commercial and government satellites alike, countries are quickly becoming more concerned with — and more motivated to forestall — reckless behavior in space.

Momentum picked up earlier this year when Vice President Kamala Harris called for the U.S. ban of destructive, direct-ascent anti-satellite weapons tests (ASATs). Harris cited the resulting space debris as a risk to global security, economy, and scientific interests, as well as the lives of astronauts in space. Her declaration is the first, but not the last of its kind, with Canada, New Zealand, Japan, and now Germany recently promising the same. Harris’ pronouncement kicked off a series of commitments from like-minded leaders and will be rolled out as a resolution at the upcoming United Nations General Assembly.

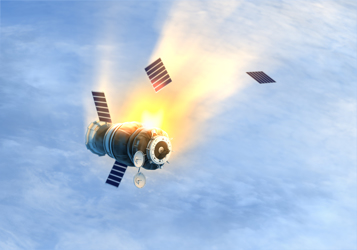

Her call to ban destructive, direct-ascent ASATs comes amidst a Russian ramp-up — wherein a series of tests were conducted in 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2021. In the latest test during November 2021, Russia deftly destroyed its defunct Kosmos 1408 spy satellite that churned up a cloud of debris dangerously close to the International Space Station, prompting criticism from the U.S. and others. Then-Air Force Gen. John “Jay” Raymond, now the head of Space Force, called it “further proof of Russia’s hypocritical advocacy of outer space arms control proposals designed to restrict the capabilities of the United States while clearly having no intention of halting their counterspace weapons programs,” according to Defense Daily.

But Russia hasn’t been the only one to try out ASATs. They debuted roughly 70 years ago. Most recently, China conducted its last test in 2013, India had its latest in 2019, and the U.S. last held one in 2008 to destroy a failed reconnaissance satellite with a hydrazine fuel tank that could’ve posed health hazards had it have survived re-entry. ASATs are tapped for a handful of reasons, including the destruction of obsolete satellites, but in recent years have been perceived as a show of force. While the U.S. claimed its test to be a safety measure, some saw it as a reaction to China’s destruction of an obsolete weather satellite.

Regardless, the U.S. maintains its commitment to peace in outer space, leading the way in demonstrating “how space activities can be conducted in a responsible, peaceful, and sustainable manner,” according to a White House report. That said, the administration also admits that “[c]onflict or confrontation in outer space is not inevitable.” And so, the United Nations is expected to forge ahead with what will reportedly become a set of norms, rather than a formalized international treaty, to address looming threats in space. A Wired report likens the approach to that of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 in which countries agreed to use space for “peaceful purposes,” keep it free from nuclear weaponry, and be held liable should they damage others’ space objects, among other concessions.

Interestingly, it was China and Russia who originally championed an international agreement regarding space weaponry, including some types of ASATs, but past U.S. administrations balked at the most recent proposal in 2014. The U.S. complained that the agreement did nothing to prevent ASAT stockpiling, did not pertain to direct-ascent ASATs, and failed to include ground-based systems. Now, under President Biden, the U.S. is taking a leading role in advocating for a set of norms.

Actions in space, as it turns out, are all in the eyes of the beholder. In those 2,000-plus kilometers from Earth, an actor’s intentions can become muddled, even lost, from the viewer’s point of view. Take the earlier mention of the U.S.’s decision to avoid harm by preemptively destroying a defunct satellite. That event was interpreted by some as a display of one-upmanship. And, though the instance doesn’t involve ASATs, consider how one Russian satellite flying too close to a U.S. spy satellite prompted U.S. space officials to call the move “unusual and disturbing” with “the potential to create a dangerous situation in space.” But, Russian officials contended the satellite was simply investigating and conducting an “experiment,” according to Time magazine.

Over the last year, there have been a handful of UN meetings on the subject, and no doubt diplomats have become antsy at finding solutions. What’s clear is that there is no more time for dawdling. What’s also clear is the need for clarity. Space behaviors are not black-and-white. What’s antagonistic to one country is exploratory to another. Despite slow starts and setbacks, the U.S. and its supporting UN members must forge ahead with proper space policy. It’s needed now more than ever.

References:

- U.S. will not conduct direct ascent anti-satellite missile tests, Harris says | Reuters

- U.S. to introduce U.N. resolution on ASAT testing ban - SpaceNews

- Japan, Germany declare moratorium on anti-satellite missile tests - SpaceNews

- FACT SHEET: Vice President Harris Advances National Security Norms in Space - The White House

- The Outer Space Treaty (unoosa.org)

- Russian Spacecraft Tailing U.S. Spy Satellite, General Says | Time

- U.S. Dismisses Space Weapons Treaty Proposal As “Fundamentally Flawed” - SpaceNews

- Space Force Official Suggests U.S. Developing Offensive Capabilities (defensedaily.com)